|

| Find it on Amazon HERE |

Thursday, August 29, 2024

New Release: I'm looking for people who can't write good - by Dan Baldwin

Monday, August 26, 2024

Louis Braille By Wayne Winterton, PhD

WHILE PLAYING IN HIS FATHER’S LEATHER SHOP, three-year-old Louis Braille tried to push an awl into a piece of leather, as he had seen his father effortlessly do many times. With his face much too close to the action, the awl slipped and, in a blinding second, the point of the tool penetrated deep into one of his eyes.

His parents rushed him to the local doctor. But in 1812, there was little hope and even less knowledge about antibiotics. The perforated eye was lost, and an uncontrollable infection ate away at the remaining eye shortly afterward.

Louis, intelligent and creative, was blind by his fifth birthday. However, he coped with his blindness well, first with help from his three older siblings and later with the use of walking canes made by his father. He attended school with sighted children until the age of ten, when he was invited to enroll in one of the world's first schools for blind children, the Royal Institute for Blind Youth.

Linguist Valentin Haüy had established the Institute in 1785 as a trade school in which blind students learned to weave and to make their own school uniforms. They made and sold items to the public, including fishing nets, chair cushions, and buggy whips. They even learned to play musical instruments and were in demand for public performances. But for Louis, the skill he treasured most was reading.

Reading was taught through a system devised by Haüy in which large books, some so heavy they couldn’t be lifted, could be read by tracing the shapes of the letters of the alphabet with the fingers. Each letter had to be felt and interpreted, the letters and words stored in the reader’s memory until the sentence was clear. Unfortunately, the first words of a sentence were often lost before the last words could be interpreted, making the system slow and inefficient.

At the time of Louis’s enrollment in 1819, the school library contained fourteen books. As slow as the reading was, Louis quickly read every book and asked, “Where are the other books that blind persons can read?”

From young Louis’s point of view, the more significant problem was that there was no way for a blind person to hand produce Haüy’s embossed characters. At 12, Louis wanted not only to read but to write as well, and he knew it had to be possible. The beginnings of that possibility were already under development by a military officer, Charles Barbier, at the French Royal Military Academy in Paris, following the annihilation of an army post when a French soldier had exposed his squad’s position by lighting a lamp to read a military dispatch.

Captain Barbier called his experimental writing Ecriture Nocturne (Night Writing), using a system loosely based on Samuel Morse’s Morse Code, in which up to eight dots and dashes were used to represent characters of the French alphabet. Barbier’s writing used an embossing tool to form the Morse Code’s dots and dashes on a moistened sheet of heavy paper.

|

| Louis Braille |

In 1823, Louis Braille and other top students demonstrated Haüy’s system at a French Museum of Science and Industry event. Captain Barbier was there to demonstrate his Night Writing to the participants. When Barbier gave Louis a copy of his system, the boy knew he had found the foundation for a language of his own. Within a year he had reduced the dots-per-character from twelve to six and begun to write on heavy paper with a pointed, awl-like stylus—not unlike the one that had blinded him as a child. It would take 100 years before the world would adopt his system. But eventually, Braille became the preferred method for written communication for the blind.

Louis Braille never left the National Institute for Blind Youth. Instead, he became one of the school’s most dedicated teachers. One week before he died in 1852, he dictated his Last Will and Testament, giving his wealth to his family and his clothing and a few personal items to his students. The will included a peculiar request: that a certain wooden box in his room be “burned to ashes” without being opened. After his funeral, when it came time to burn the box curiosity got the best of his family. Opening it, they found hundreds of promissory notes in Braille from students who had borrowed money from their generous teacher over the years.

|

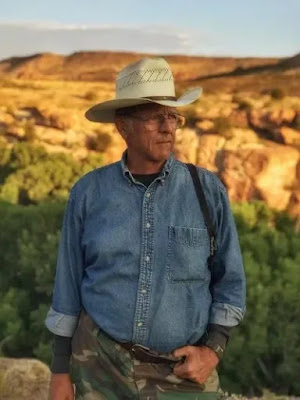

| Wayne Winterton, PhD |

Wayne Winterton began his career in 1963 as a public school teacher, and later as the principal of two schools on the Navajo Reservation (Lake Valley, and Dzilth-na-o-dith-hle). He was also the Superintendent of the Albuquerque Indian High School, the Superintendent of Schools for the Northern Pueblos Agency (northern New Mexico), and during 1978-79, he served as the interim President of the Institute of American Indian Arts, a junior college in Santa Fe. In 1986, he joined the staff of the Bureau of Land Management’s National Training Center in Phoenix as the Division Chief for Administrative and Media Services, and later, as Center Director before his retirement in 2004 with 41 years of public service.

Tuesday, August 13, 2024

Polishing the novel, my favorite part of the writing process - by Vijaya Schartz

After lots of research, after sweating the plot, the character motivations and conflicts, the surprises and roadblocks along the way, the setting, the technology, and all the details that come into creating a good story, my favorite part of writing is what some writers hate: the “rewriting.” I prefer to call it “Polishing.” It’s an opportunity to take a story and make it better.

|

| amazon - B&N - Smashwords - Kobo |

Monday, August 5, 2024

New Release: Nostalgia - Stars of Yesteryear - by Jack Hawn

|

| Find it on Amazon HERE |

Now in the twilight of my writing career, I decided that a third book following Blind Journey: A Journalist's Memoirs and its sequel, Insomnia: Two Wives, Childhood Memories and Crazy Dreams, would simply be too much work.

Among the fifty-plus articles in my book, Nostalgia: Stars of Yesteryear, is a feature on the McGuire Sisters, one of my best-loved trios.

Titled “An Unforgotten Affair—Las Vegas, 1985” the story details my meeting with the ageless trio in their Hilton Hotel room.

I met the McGuire sisters—the "Sugartime” sweethearts—when they returned to the spotlight, appearing at the Las Vegas Hilton after a 17-year hiatus. For Christine, Phyllis, and Dorothy, it was as if time had stood still. Sleek, sexy, and glittering as always, they still harmonized like angels, chattered like giggly teenagers, and drew packed houses wherever they performed.

When I stepped off the elevator on the 29th floor of the Hilton en-route to interview them, I was escorted to their suite by a gun-packing bodyguard. The sisters were extremely security-conscious then, courtesy of an erstwhile link with the underworld—Phyllis' legendary love affair with Mafia boss Sam Giancana.

Phyllis wasn't opposed to providing details of how she had met him and been almost immediately hooked by his charm. It had been an exciting relationship, but she didn't dwell on it. She had loved him. Period.

For her sisters Christine and Dorothy to remain silent while the leader of the trio dominated the interview was impossible. After seventeen years of virtual silence following Giancana’s murder in 1975, all three had a lot to update— sometimes all speaking at once.

Besides being one of my favorite trios, those beautiful, bubbly, non-stop talking young women were one of my favorite interviews recorded in this book.

Thursday, August 1, 2024

My Name Ain’t Nobody by Dan Baldwin

I recently heard a new-ish writer complain that “nobody knows me, so I’ll never make it as a published writer.” That last bit about making it may be true. Success depends on many factors, but being a nobody isn’t one of them—unless the writer decides to make it so. At one time nobody had ever heard of Mark Twain, Hemmingway, Harper Lee, Jack Kerouac, Isaac Asimov, or Stephen King. As writers each of us starts from the same starting line of public awareness. Such awareness requires that the writer accomplish five basic tasks.

#1: Write a good story. That’s easy in the sense that writing is a joy; it’s the easiest job in the world. Writing does require discipline. To enjoy, and I mean to really enjoy the fun of writing, you have to have a daily schedule and you have to stick to it. Writing well develops over time, and the skill improves with age. The more you write, the better writer you become.

#2: Share the wealth. The worst judge of a writer’s work is the writer. The success of the work depends on the readers, on the market. It’s important for the writer to forget any qualms about being good or successful or recognized. Publish! Put the work on the market, forget about it, and move on to the next story.

#3: Become your own force multiplier. A force multiplier is something that increases the power of a single person, unit, or army. A writer’s force multiplier is his ability to produce more work. One-hit-wonders occur, but that’s no way to earn a living, support a lifestyle, or become known as a successful writer. Once readers find your story—and some will— they will want more. It’s the writer’s job to make sure that their readers’ desire for more is fulfilled. If they can’t find more, they move on to someone who is more disciplined and who produces sequels, prequels, and a continual stream of new works.

#4: Play the long game. Publishing today is easier, faster, and more profitable for the author than at any time in history, but the writer seeking fame and a fast buck will be disappointed. I can write a novel and have it published around the world within 30-45 days of handing the manuscript over to my designer/formatter. But my thinking is never focused on weeks or months. I think in terms of years—and I mean five-years-down-the-road thinking.

#5: Call your own shots. As noted, you must write to a schedule. Study writing, publishing, marketing, and something completely removed from writing (to keep your mind stimulated). Learn the ins and outs of publishing. The publishing world is still in turmoil over the Indie publishing revolution. As hustler Tony Curtis said in Operation Petticoat, “In confusion, there is profit.” Thanks to this confusion, writers have more options than ever. Use them to your advantage. Learn all you can about contracts and copyrights, covers and formatting, promotion and marketing. It takes time, and it’s all part of playing the long game.

Remember, each of us bolts from the same anonymity at the literary starting line. How far you go after the starter’s gun depends solely on you.

The author of westerns, mysteries, thrillers, short story collections and books on the paranormal, Dan Baldwin has won numerous local, regional, and national awards for writing and directing film and video projects. He earned an Honorable Mention from the Society of Southwestern Authors competition for his short story Flat Busted and was a finalist in the National Indie Excellence Awards for Trapp Canyon and Caldera III— A Man of Blood. A finalist in the New Mexico-Arizona Book Awards for Sparky and the King, Baldwin won the 2017 Book Awards for Bock’s Canyon. His paranormal works are The Practical Pendulum—A Swinging Guide, Find Me as told to Dan Baldwin, They Are Not Yet Lost and How Find Me Lost Me—A Betrayal of Trust Told by the Psychic Who Didn’t See It Coming. They Are Not Yet Lost and How Find Me Lost Me both won the New Mexico-Arizona Book Competition. More at www.fourknightspress.com and www.danbaldwin.comI am not concerned that I am not known. I seek to be worthy to be known. —Confucius